Aerospace and satellite companies are urging governments around the world to adopt a “highway code” to tackle space junk.

The Space Safety Coalition (SSC), an international organisation of satellite operators, aerospace companies and industry representatives, has published new guidelines to protect satellites orbiting the Earth from being damaged by space debris.

In it, the coalition calls for a rules-of-the-road-style guidebook for manoeuvring spacecraft to avoid collisions.

Rajeev Suri, chief executive of British satellite telecommunications company Inmarsat, which is one of the 27 signatories to the SSC, said: “Initiatives like the Space Safety Coalition are an important step towards establishing international best practices and guidelines to protect the space environment, but it is not enough.

“The clock is ticking, and real action is needed.

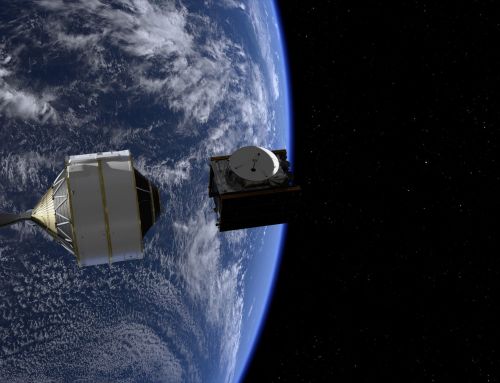

New ADRAS-J video!

The ADRAS-J mission will be the world’s first attempt to safely approach and characterize an existing piece of large debris and is the start of a full-fledged debris removal service.

Check our mission page for more info! https://t.co/KoEci0aBRh pic.twitter.com/4dVBClpRAQ

— Astroscale (@astroscale_HQ) March 30, 2023

“National regulators everywhere should now use their powers of granting market access to require that satellite operators adhere to best practices like those outlined by the Space Safety Coalition and beyond.”

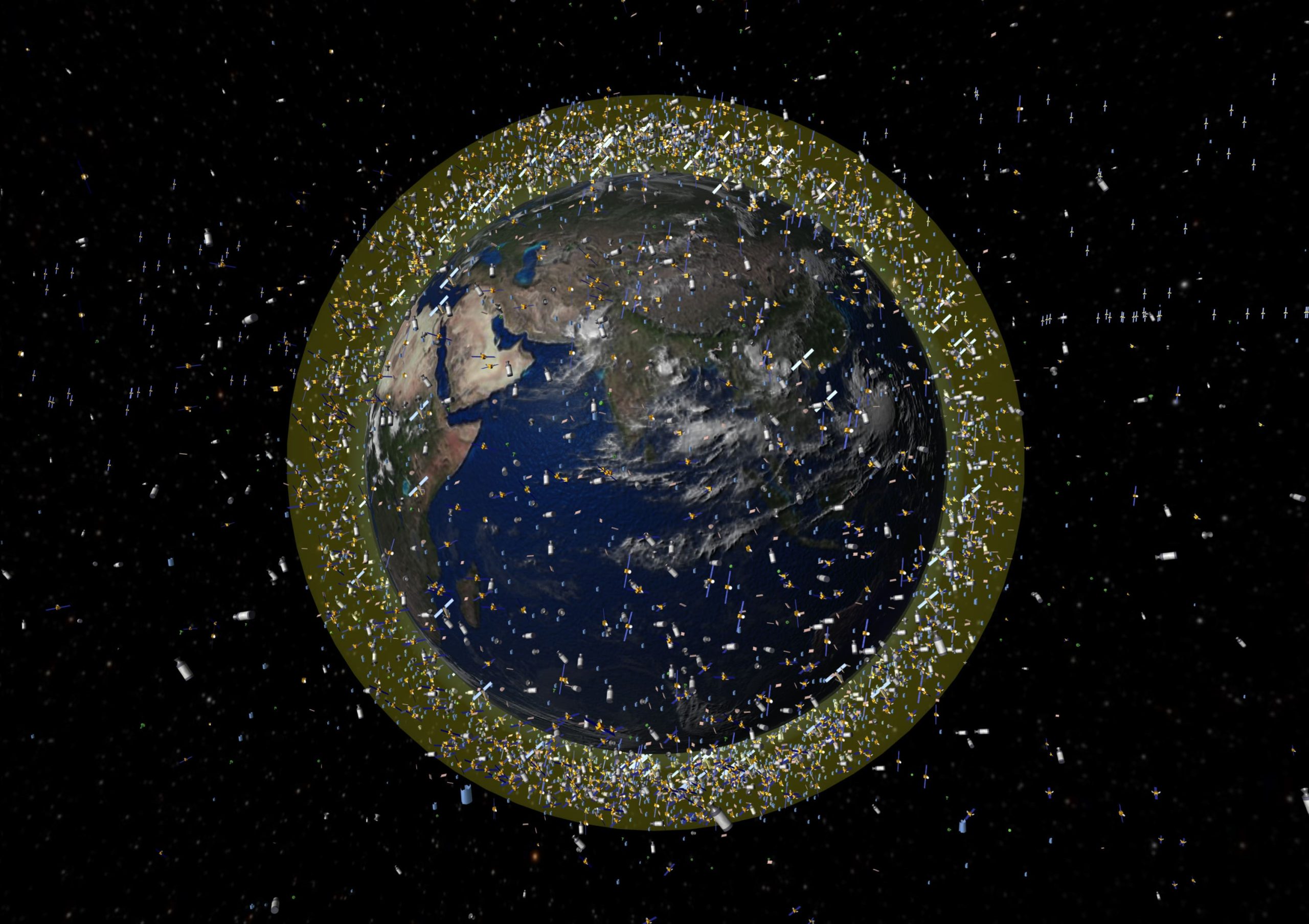

Since the first orbital launch in 1957, the number of artificial objects in low-Earth orbit has been growing.

The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates there are 36,500 objects larger than 10cm currently floating in space, alongside 130 million pieces of space debris between 1mm to 1cm.

These objects are thought to move at speeds of more than 10,000 km per hour (6,200 mph), posing a risk to operational satellites in orbit.

Meanwhile, the number of satellites in orbit is expected to rise from about 9,000 today to nearly 60,000 by 2030.

Collisions are rare at the moment but, as more satellites make it into orbit, it raises the need for a lot more collision avoidance manoeuvres.

In 2018, Surrey Satellite Technology’s RemoveDEBRIS mission practised grabbing a satellite with a giant net.

A year later, ESA performed its first satellite manoeuvre to avoid colliding with a mega constellation.

Meanwhile, UK-based Astroscale, also a signatory to the SSC, is planning the UK’s first national mission to remove space debris.

In its guidelines, the SSC has also laid out the best practice for space operators, which include international information-sharing between spacecraft owners, operators and stakeholders to avoid future collisions; avoiding intentional space object fragmentations or collisions that place other nations’ satellites or crew at risk; and prioritising sustainable practices during satellite launches, for example using re-usable launch vehicles or alternative fuels.

Ray Fielding, head of sustainability and active debris removal at the UK Space Agency, said: “The growing issue of space debris and the avoidance of hazardous conjunctions is one of the biggest challenges facing the global space sector, and one of the key priorities of our National Space Strategy.

“The UK Space Agency has committed £102 million over the next three years to build capabilities for tracking objects in space and developing technologies, regulations and operating standards to reduce the risk posed by current and future debris and make space more sustainable for all.

“We are also backing the UK’s first national space debris removal mission launch in 2026 and have recently launched the monitor your satellite service which gives collision warning information to UK satellite operators.

“Ensuring a safe and prosperous future in space for everyone also requires a balance of regulation and sustainability standards that encourage economic development while reducing the risk of space debris in the first place.

“The UK is leading the way in these conversations, thanks to the positive ambitions of those involved in the Space Safety Coalition.”

Commenting on the report, James Blake, research fellow at the University of Warwick’s Centre for Space Domain Awareness, added: “Despite widespread acknowledgment of the severity of the space debris problem and the risk it poses to active satellites, we still see very little adherence to mitigation guidelines.

“These new guidelines represent a positive step forward, but with tens of thousands of satellites licensed to launch into an already crowded environment over the next decade, operators must take note to prevent the situation from worsening.”