The most distant star ever seen has been observed by astronomers, who say the discovery could unlock secrets of a still-unknown era of the universe.

The light from the star has taken some 12.9 billion years to reach Earth, much more than the nine billion light years of the farthest “supergiant” previously observed.

Scientists said they were surprised by the distance of the star, which they have named “Earendel”, meaning morning star in Old English.

Dr Guillaume Mahler, from Durham University’s Department of Physics and Centre of Extragalactic Astronomy, said: “This might be the earliest star we will ever see since the Big Bang and it was so surprising that it is so much younger than the previous entry of nine billion years, at first I didn’t believe it.

“The discovery of Earendel is fantastic and there will be many other aspects of the star we will be able to study, which could keep us busy for years to come.”

The findings of the international team of researchers were published in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

They made the discovery with Nasa’s Hubble Space Telescope, using data collected during its reionisation lensing cluster survey (RELICS) programme.

They said that if Earendel is a single star, it would be at least 50 times the mass of the sun and millions of times as bright, making it one of the most massive stars known.

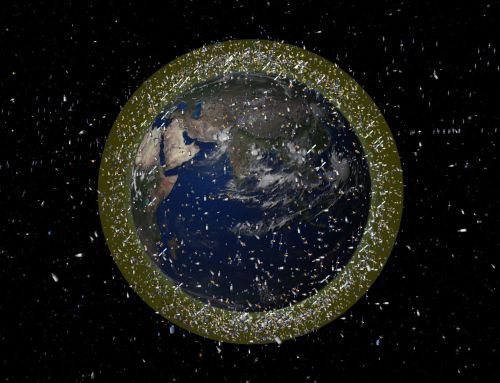

But even such brilliant stars would be impossible to make out individually with telescopes without natural magnification provided through an effect called “gravitational lensing”.

It occurs when massive galaxy clusters warp the fabric of space, greatly amplifying the light from distant objects behind it.

2/ Learn about Gravitational Lensing from our 📖 #HubbleWordBank: 🔗 https://t.co/yGgIjzF5a6

Credit: @esa / @HUBBLE_space / @NASA / S. Jha

— HUBBLE (@HUBBLE_space) February 2, 2022

In this case, a rare cosmic alignment with a huge galaxy cluster, sitting between Earth and Earendel, meant the star’s brightness was magnified by a factor of thousands, allowing astronomers to see it.

The lensing phenomenon, predicted by Albert Einstein, is the result of a massive object bending space-time around it and forcing light beams to take a curved path.

Dr Mahler said: “Gravitational lensing is like observing galaxies under the microscope and with technology such as the Hubble telescope, you start to see what is inside.”

PhD student and lead author Brian Welch, from Johns Hopkins University, said: “We almost didn’t believe it at first, it was so much farther than the previous most distant star.

“Normally at these distances, entire galaxies look like small smudges. This galaxy has been magnified and distorted by gravitational lensing into a long crescent that we named the ‘Sunrise Arc’.

“Studying Earendel will be a window into an era of the universe that we are unfamiliar with, but that led to everything we know.

“It’s like we’ve been reading a really interesting book but we started with the second chapter, and now we will have a chance to see how it all got started.”

Scientists expect Earendel to remain magnified for years and it will be further studied using Nasa’s Webb Space Telescope, which has a high sensitivity to infrared light.

That makes the telescope suitable for observing the star’s light, which is stretched to longer infrared wavelengths due to the universe’s expansion.

Co-author Dan Coe, from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said: “With Webb we expect to confirm Earendel is indeed a star, as well as measure its brightness and temperature.

“We also expect to find the Sunrise Arc is lacking in heavy elements that form in subsequent generations of stars. This would suggest Earendel is a rare massive metal-poor star.”

Selma de Mink, scientific director of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics and co-author of the paper, said: “It is kind of like finding an old photograph of your great-grandparents, because these stars are basically our ‘stellar ancestors’. We are, after all, made out of the elements that they once produced. Yet we have so many unanswered questions.

“Most exciting for me is that some of the black holes recently detected by gravitational waves are remnants of stars that lived back then. I hope that Earendel and future similar discoveries will help us understand a little more about the origin of these black holes.”